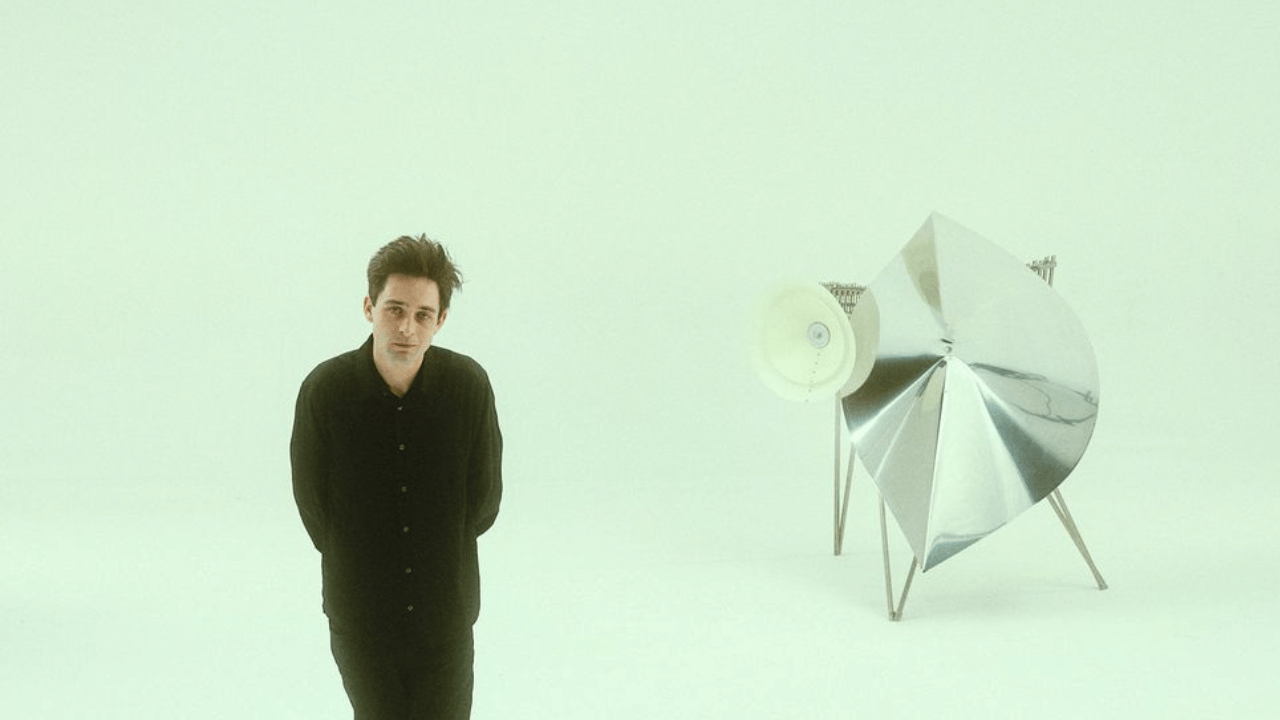

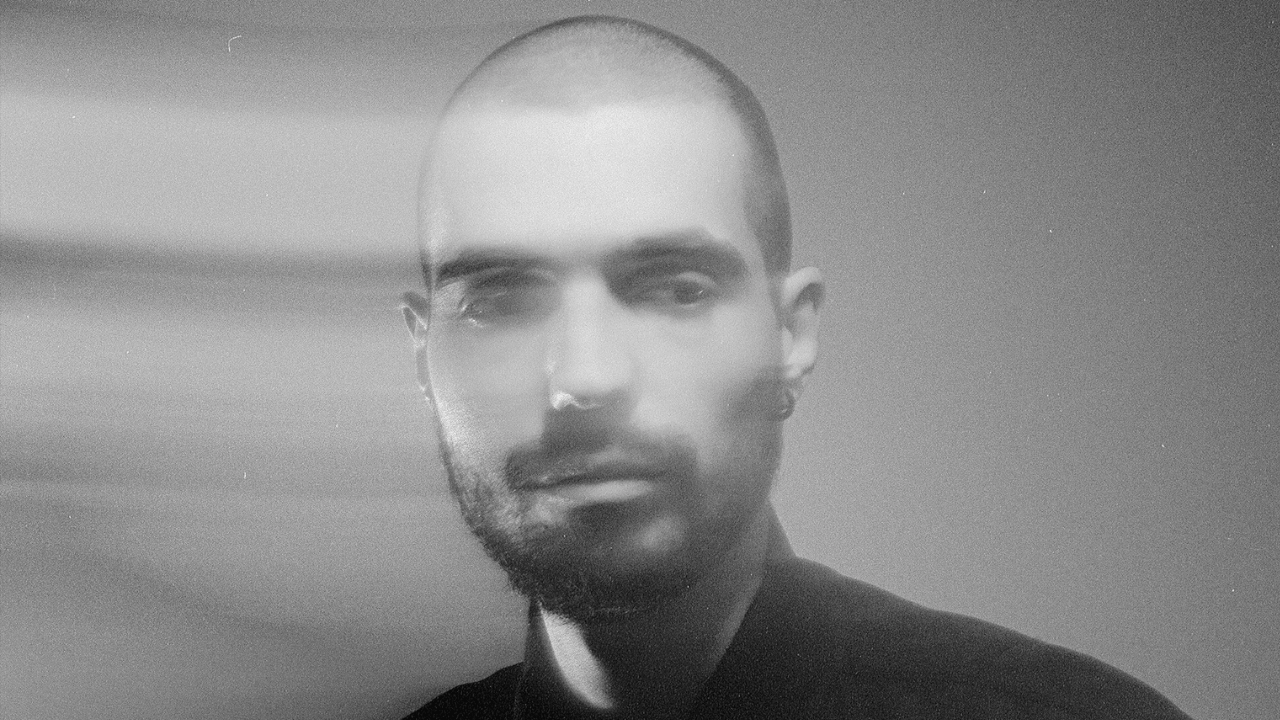

Hi Mike, can you shortly introduce yourself?

I’m Mike Sheridan, b. 1991, Danish/Irish Copenhagener, autodidact music maker and musician, fascinated with experimental sounds and general zen.

How did you first become interested in electronic music? What drew you to this genre, and when did you start producing your own tracks? Also, tell us a bit about yourself at that age and the environment you grew up in.

I started being interested in hip hop as a teenager, so I got into DJing with vinyl records at a local music school. Growing up in Amager [neighborhood in Copenhagen], there was not so much to do, so I spent most of my time with my mom, dad, our family dog, and skateboarding with my friends.

I first heard electronic music on national radio as a teenager, and I remember being awestruck by it. It coincided with me coming of age. Music became a form of guiding star for me. It liberated me to explore something out of the confines of normativity.

As a kid, I felt exhausted by larger social settings; hence making music with the computer gave me a real sanctuary. I loved listening to the radio until 3 in the morning, and still, when time clocks past midnight, my mood just ticks upward with the solitude of night.

Looking back at the beginning of your musical practice, what key moments or influences helped shape your path as an electronic musician?

I uploaded my music online around 2004 and began to connect with DJs and other music makers. I looked forward to getting home from school to check my DMs and see who’d written or responded. This is 00’s internet, before social media. I used it as testing grounds and a way to shape my artistic identity when I started.

The most defining moments came through the older generation, who’d already established themselves. They asked me to play and perform, and I got to learn about the scene. I was the only one at the time at my age, so learning how to take responsibility for my talent came from being given opportunities. I’ve always been very, very grateful for that.

If someone has a flair for something at an early age and there is nobody there to encourage them to put it to work and make it count, there is a huge chance that the talent is discouraged from taking it further. It needs to be supported at that critical point of acceleration.

As you dive into a new project, what practices do you engage in to prepare yourself? Are there specific routines that help you get into the right mindset?

What works for me is to have distinctive creative passes where I perform and record; this is followed by more analytical passes where something like an architectural blueprint is what I’m aiming for. I find the most valuable ingredient to be time—not too much and not too little, just enough to make out what’s going on from pass to pass. At a certain point, I step away from the work, which in a sense consolidates the first part of a project. With this, I’m quite methodical.

What I work with is to create a space where I can experiment and try and make something that excites me deeply. My goal is to make the process exciting and let the hours fly by in the best possible way.

Over the years, have you developed any techniques that assist you in maintaining your focus? How do you approach creative blocks when they arise? Are there any non-musical fields you dive into to find inspiration or regain motivation?

I’ve been blessed with an ability to hyperfocus. If I get a creative block, I know that it’s often just a matter of working through it. Just do more; start ten new DAW projects and do whatever comes to mind—progress. My mind plays tricks on me all the time, and it does happen that I check yesterday’s work and find it now has an immediate quality.

I do hear distinctive soundscapes for my inner ear that try to materialize when I work. The best way I can describe it is that it feels like a memory that appears but with energy—it’s psychosomatic. When I work, it’s that energy I use as the litmus test.

I am not very reactive in my music; it is not a place where I work with insecurities or where I want to demonstrate some form of virtuosity. What I work with is to create a space where I can experiment and try and make something that excites me deeply. My goal is to make the process exciting and let the hours fly by in the best possible way.

How has your exploration of new instruments and technologies influenced your musical practice? What motivates you to experiment with unconventional tools or systems?

I am dyscalculic, so the more mathematical things get in terms of systems, the more I counter. Everything with me is by ear and based on intuition, so instruments become extremely important. I was always jealous of instrumentalists when I was younger. When I’d pick up the guitar or play the piano, I liked the reverberations, soundings, overtones, or noises more than playing chords or songs. It was kind of confusing initially, but I had to accept that playing songs just wasn’t my thing at all, and I could find no motivation whatsoever for practicing. This did, however, encourage me to see if I could find instruments that in turn really spiked something in me.

Eventually, I found that with the Cristal Baschet. It’s an incredible sound-sculpture from France that was invented by Bernard and Francois Baschet as an acoustic complement to the musique concrète style of the 1950s and 60s. You play it with wet fingers and hands as the keyboard is made from crystal glass rods. You actually bow the rods, and it gives you total control over the sustain. The rest of the instrument is metal, with the exception of one type of acoustic speaker that is made from composite fiberglass. Metal is a very dense material and produces the richest harmonics; thus the Cristal becomes a form of acoustic synthesizer. I was 19 when I started playing, and my relationship with the instrument is developing all the time.

How has working with modular synths shaped your approach to composition and performance?

I started out with Eurorack and had two cases of modules back in 2010. I eventually sold it in favor of a Buchla 200e. The Buchla was like a mystery that I had to solve. I did also have a Serge system for a long time. Both systems were fantastic instruments for me to own and perform with. Ultimately, I felt that they were maybe too idiosyncratic for the music that I wanted to make, and I made a hard call to clear out my inventory. The best part of having spent so much time with Buchla and Serge is that their designs really made me so much more creative about how to think about electronic sound generation. They do this by forcing you to abandon your conventional approaches and instead they say, “try this!”

I felt amputated for a long while with the two systems gone, yet I spent time properly evaluating what I wanted from an electronic instrument at this point in my work. Lightning did eventually strike, and I chose this modern interpretation of the EMS Synthi, the Portabella made by Pin Electronics in Germany, which is simply incredible.

Composing and performing have previously been two different disciplines in my practice, but I now see them being much, much more connected. In that sense, there is an interconnectedness between the different areas of my practice, which informs all the moving parts continually.

I have only one analog synthesizer at the moment, which is the Pin Portabella. I immediately paired it with the Torso T1, which is like a modern KS and very reminiscent of the Buchla 250e sequencer that I adored. Together with the S4 platform, it forms the synth-station.

What is your current setup? And how do you incorporate the Torso Electronics instrument into that?

My current lab is centered around my Apple MacBook Pro running Ableton and Pro Tools. I have an RME Fireface UCX and a pair of Genelec 8331 with SAM. The Cristal Baschet is also always set up for me to play.

I have only one analog synthesizer at the moment, which is the Pin Portabella. I immediately paired it with the Torso T1, which is like a modern KS and very reminiscent of the Buchla 250e sequencer that I adored. Together with the S4 platform, it forms the synth-station.

Last year, I decided to get back into playing guitar. As I mentioned earlier, I recall from my childhood that playing guitar just never really fell into place. I couldn’t find my own way with it, but I found that I just missed it a great deal. I got my hands on an aluminum guitar from Obstructures, the 0.750, which has a never-ending sustain and, as they proclaim: “it is made for people who don’t really play guitar.” I play it with the heaviest gauge flatwound guitar strings I can find.

Around the guitar, I put together two pedalboards; one is a tone and effects board, and the other is inspired by tape looping, digital sampler-delays, and made to play with stereo amps. Still working on finding the best solution for the first board, but the sampler-delay-loop-fx board has really become a favorite instrument in itself now.

There is also the virtue of great patience, as it takes time to make art. I’ve tried collaborating when it gets exhausting and all breaks down, as well as it being the most uplifting thing in the world.

What do you enjoy about collaborative work, and how does it challenge or push you?

Ideally, collaboration brings me somewhere that I can’t imagine all by myself. To me, that’s the criteria of success. I consider it an exchange of gifts. I’ve collaborated with other artists in music, in film, and on stage, and meeting other committed individuals that open up about who they are, what they dream about, and share their craft is always incredible.

Hence my point about generosity: The quality I try to bring and look for in collaborations is if all involved parties are prepared to bring each other gifts. There has to be a desire to participate generously. These gifts combined are what ultimately gestalts the finished work.

I’ve myself been guilty of forcing a certain vision through at times, and it just doesn’t feel great afterward. Don’t get me wrong; there is nothing wrong with creating a sense of direction, but listening and facilitating the process of bringing out the quality in other people’s ideas—that’s what kicks.

There is also the virtue of great patience, as it takes time to make art. I’ve tried collaborating when it gets exhausting and all breaks down, as well as it being the most uplifting thing in the world.

These days, I’m interested in how what I do can add a dimension to other artistic fields, and it has been lovely to work with visual artists such as Nicolai Howalt and Nadja Brecevic. I feel there are very close ties between music and especially photography, of which Nicolai and Nadja are primarily working with. Those projects have been great personal highlights for me

Looking ahead, from which other art forms do you find inspiration at the moment, and what do you find interesting to explore in the future?

Dance and film are on my current horizon, both fields that are really dear to me and that I enjoy doing. We Need To Find Each Other by Brian CA will premiere at KulturFabrik in Luxemburg in Q1 of 2025. The film is an independent documentary by a good friend of mine.

I have a personal project lining up that I’ve been steadily cultivating—but for now, that’s going to be the cliffhanger of this interview.

Thank you for all the great questions; it’s been an absolute pleasure!

Learn more about Mike Sheridan:

www.instagram.com/mikesheridandk

www.facebook.com/mikesheridanmusic

https://mikesheridan.bandcamp.com/album/atmospherics

Videoes by Spektrals, Photos by André Hansen